“To be blunt, I hated Steve McMahon”

As the managers countdown draws to a close Alex Cooke delves behind my statistics to present his case for who is the worst Swindon Town manager.

The numbers are clear: Paul Hart is Swindon Town’s worst manager. His managerial reign could be described as a car crash – except at least a car crash is compelling to watch. But the statistics couldn’t be clearer if they flashed out their warning in 64 font accompanied by a honking great klaxon: Hart was a disaster.

However, the numbers don’t include context. These statistics only measure results, not the climate in which those were achieved, and are three points always equal? Can we truly say it was equally easy for Iffy’s administration-hobbled, quickly cobbled collection of loanees, gimmers and youth players to earn a win in third tier in 2005/06 as it was for the heavily resourced Danny Wilson five years later?

Too much had changed at Swindon Town, and in football generally, to make such purely numeric comparisons valid. Instead we need to look at those managers who we’ve seen with our own eyes, who we’ve seen fail to achieve given the money, time and and the opportunities to succeed – and by that measure Paul Hart is still bad, but far from the worst offender.

In many ways this article should twist its many pointed adjectives into an electronic fist to repeatedly smack John Gorman around the moustache. For Gorman had the unprecedented chance to establish Town as a Premier League club, and failed. He then had a chance to solidify Swindon’s position as a Championship (then Division One) side, and failed. He had a talented team but over two seasons failed to fix the obvious flaws, instead making a number of woeful signings on hefty wages, including the hairy, the homesick and the plain hopeless.

However, the most terrible element about Gorman’s reign is that it was the high watermark for Swindon Town in modern times. For what followed Gorman was nothing but decline, and that decline was presided over by Steve McMahon.

In fact, decline was written throughout the McMahon era like a misprinted stick of rock. For under McMahon everything gradually got worse: the football, the results, the players, the attendances and the club’s relationship with the fans.

In fact, decline was written throughout the McMahon era like a misprinted stick of rock. For under McMahon everything gradually got worse: the football, the results, the players, the attendances and the club’s relationship with the fans.

We must largely ignore the initial excellence of his first full season in charge as that masks the truth and distorts the statistics. Anyway, he largely got the team relegated in the first place.

For, once relegated, McMahon began with his time in charge with a good side, bolstered it with excellent signings and played some delightful football. However, he ended it with a workman-like team where the brutality of the likes of Darren Bullock had long overshadowed the beauty of Mark Walters.

Each season that followed mirrored this theme, starting with a string of superb results and ending with a long limp from the arse-end of winter as a top half position turned into a bottom half struggle with very few goals scored. His signings went in the same direction too – from Finney and Culverhouse to Holcroft and Elkins – as his policy of recruiting people he used to play with saddled the club with overpaid, and often overweight, hasbeens.

He also seemed to want to expunge the history of Swindon Town, just in case anyone dared to eclipse him. So he removed Andy Rowland and John Trollope from the backroom and exiled players such as Taylor, Bodin and Digby with the terrible efficiency of a dictator disappearing his rivals in the night.

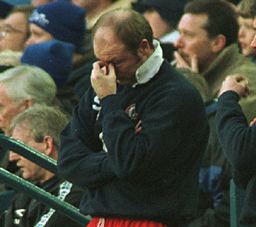

To be blunt, I hated Steve McMahon. Saying it now so many years later might seem faintly silly but I certainly wasn’t alone. Perhaps it was the spread of the internet, the strength of fanzines at the time and the larger crowds we used to get back then but McMahon seemed to invite mass opprobrium, and to almost revel in the anger. And if the rumours were true, he provoked the same feelings in the dressing room too.

Similarly his shifty, blinky interviews made him seem evasive but he also displayed utter self-regarding arrogance and aggression in place of empathy as he moved on one club legend after another, much like a pissy Dalek.

McMahon also provides us with a troubling example: he was manager with a great playing career behind him, a man of passion, conviction and certainty. He was given the resources to reshape the club, both on and off the field, and yet this freedom, this lack of constraint from the board or his bootroom, meant that once things had started to go array, he lacked the experience, the empathy, the knowledge, or the flexibility to change things. Let’s just hope that whatever Paolo Di Canio’s statistics eventually prove they show that McMahon was a one-off.

Follow Alex on Twitter @AlexJamesCooke

Just stumbled across this. Great blog. God, I hated McMahon too.

LikeLike

Pingback: At Fifteen in Thirteen « Picture of Football

Pingback: At Fifteen in Thirteen « Football Fans Downunder

Steve McMahon was the reason I stopped going to watch Swindon Town play. Thank Goodness I won a pair of season tickets last season!

LikeLike